Molly guard in reverse

Old-school computing has a term “molly guard”: it’s the little plastic safety cover you have to move out of the way before you press some button of significance.

Anecdotally, this is named after Molly, an engineer’s daughter who was invited to a datacenter and promptly pressed a big red button, as one would.

Then she did it again later the same day.

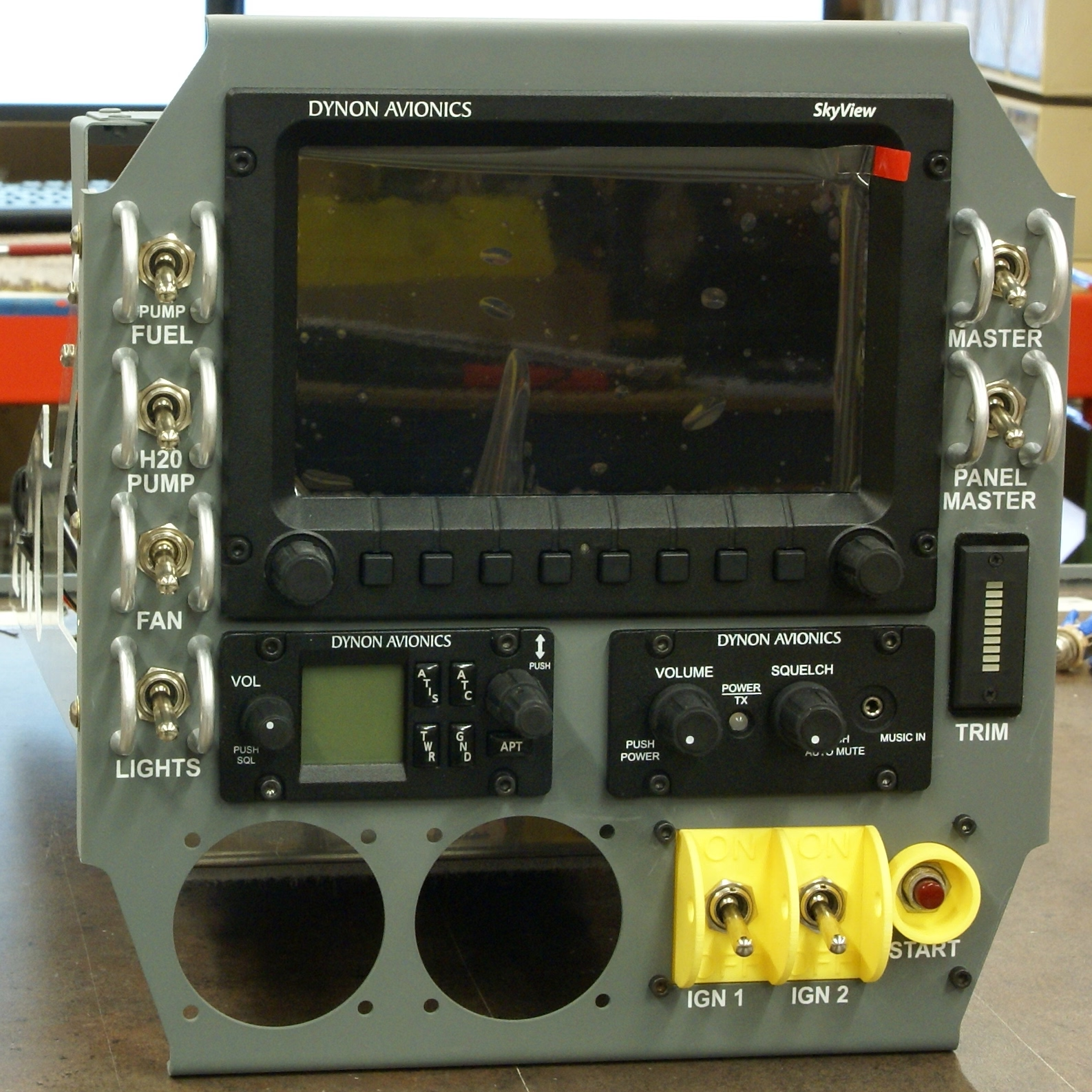

You might recognize molly guards from any aerial combat movie you ever watched:

And some vestigial forms of molly guards exist everywhere in civilian hardware, too: from recessed buttons, through plastic ridges around keys, to something like a SIM card ejection hole.

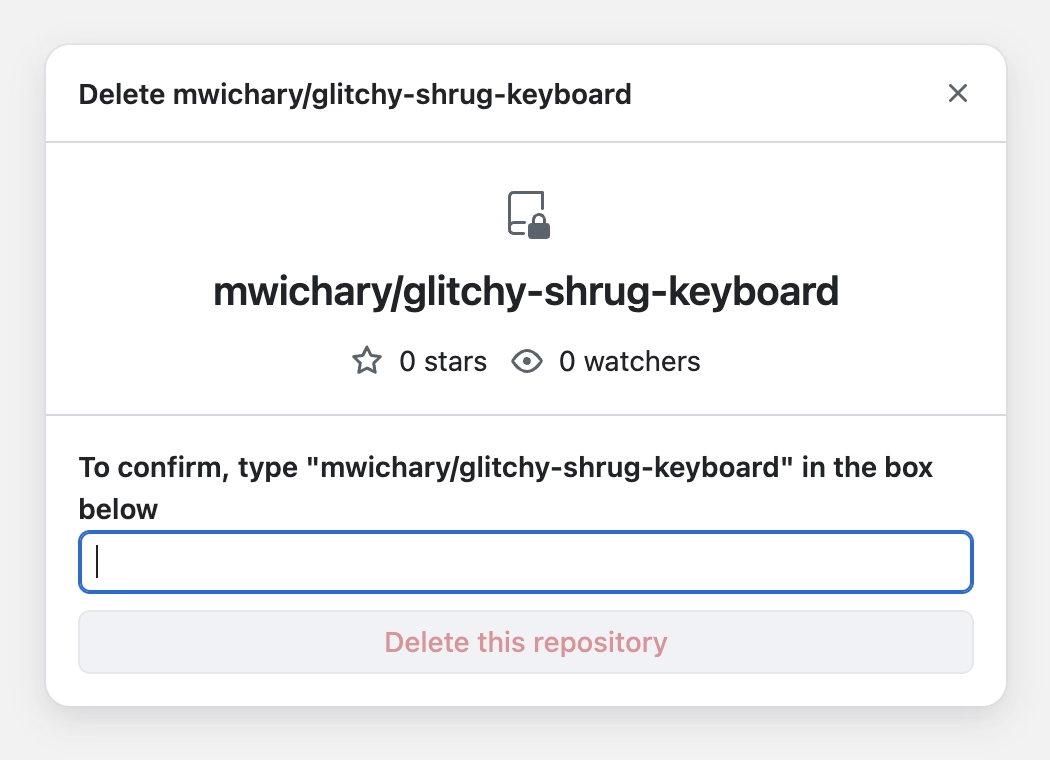

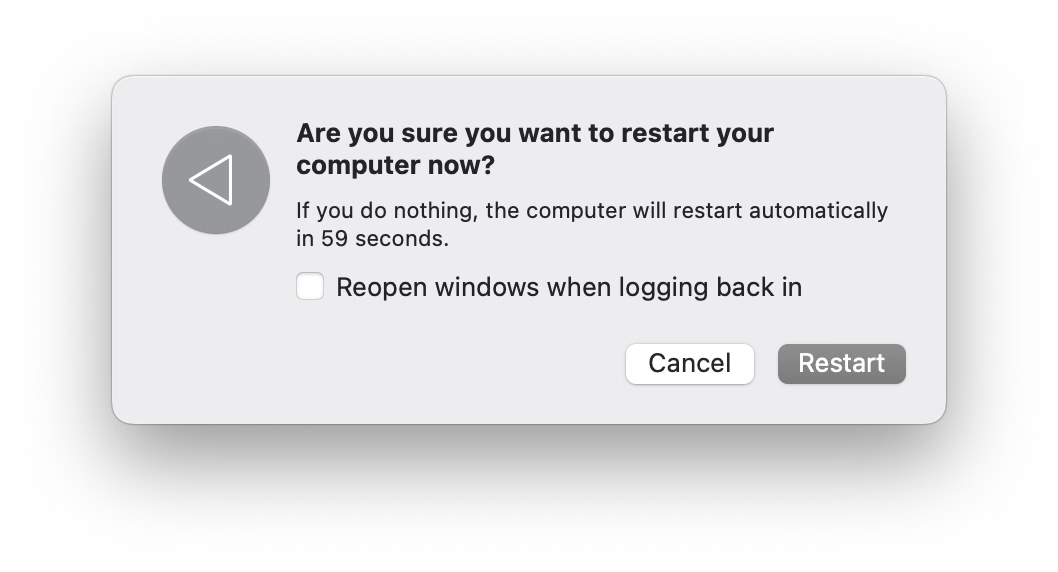

Of course, molly guards happen in software, too: from the cheapest “are you sure?” dialogs (which sometimes move buttons around or disable keyboard activation to slow you down), through extra modifier keys (in Ctrl+Alt+Del, the Ctrl and Alt keys are the guards), to more elaborate interactions that introduce friction in places where it’s needed:

But it’s also worth thinking of reverse molly guards: buttons that will press themselves if you don’t do anything after a while.

I see them sometimes, and always consider them very thoughtful. This is the first example that comes to my mind:

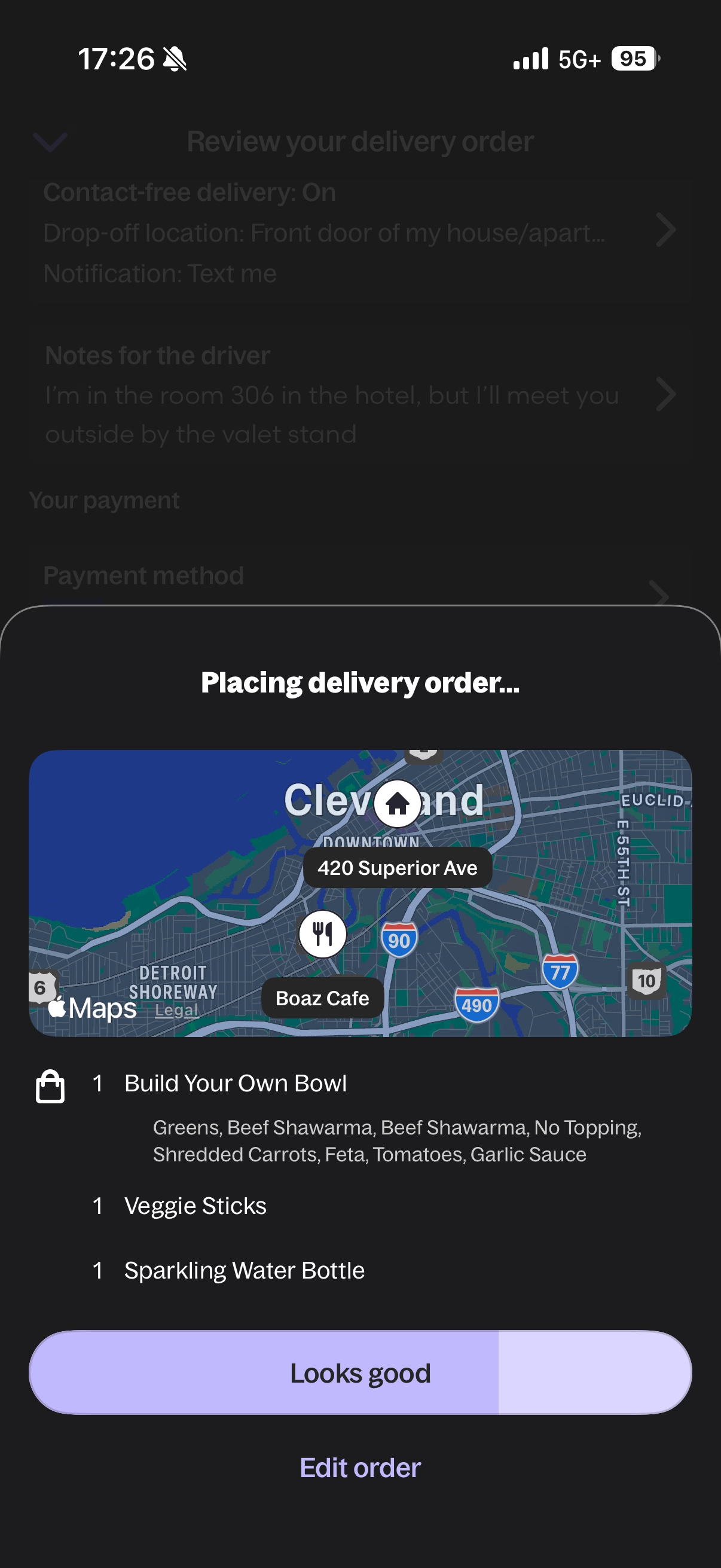

Here’s what became a standard mobile pattern:

These feel important to remember, particularly if your computer is about to embark on a long process to do something complex – like an OS update or a long render.

There is no worse feeling than waking up, walking up to the machine that was supposed to work through the night, and seeing it did absolutely nothing, stupidly waiting for hours for a response to a question that didn’t even matter.

It’s good to think about designing and signposting those flows so people know when they can walk away with confidence, and I sometimes think a reverse molly guard could serve an important purpose: in a well-designed flow, once you see it, you know things will now proceed to completion.